Transcript of a talk I gave on my Father, Mother, Daughter project, at the 15th annual Deleuze Conference, held at the Institute of Philosophy and Social Theory, Belgrade, Serbia, July, 2023.

Father, Mother, Daughter

an experiment in thinking

Derek Hampson

This presentation is a record of an art-philosophy project, a meeting of a practice of art and a practice of thinking, which has led to the creation of five bodies of work, combining painting, printmaking, drawing and writing. The first two bodies of work are theorised through the writings of Martin Heidegger; the following three bodies of work are theorised through the writings of Gilles Deleuze.

My aim in this presentation is two-fold, to understand the changing place of theory in relation to my practice, and, to understand these works as a totality, i.e. as a whole made up of parts. This totality and these parts are presumed to have a structure, the criteria of which are: symbol, sense, singularities, paradoxical elements and series; all of which will be seen to play a part in my theorisation of these works. How parts and whole are connected is the problem of structuralism, a problem which circulates in this project; expressed in its primary question, how do we go from thought to practice?

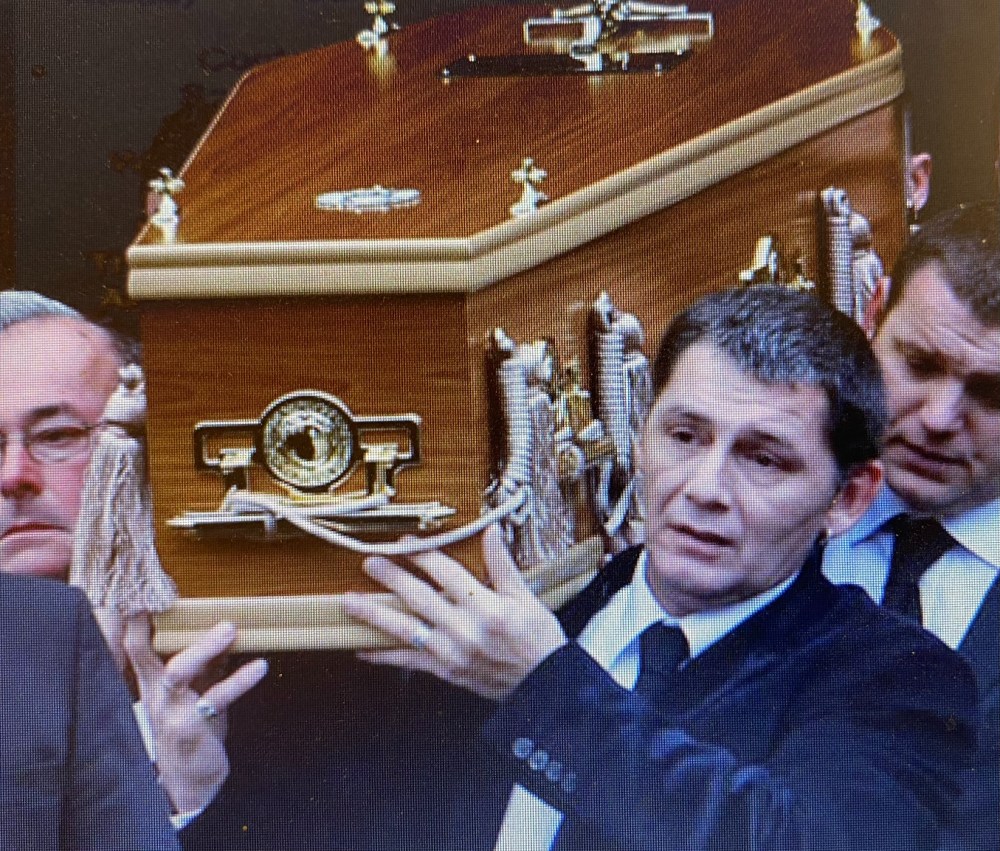

This project starts from a newspaper story, which tells of a family, the father, mother, daughter of the title, pulled apart by violence, brought on by an uncontrolled use of drink and drugs. In outline, the story tells of a drunken argument between the father and a neighbour, over a broken table, which ends with the father killing the neighbour with a knife. This is witnessed by the daughter, who, unable to bear what she has seen, commits suicide by jumping from a bridge. Her suicide is followed by that of her father, leaving the mother to grieve the loss of both.

This project, therefore, begins from a series of what Deleuze calls singularities, the ramifications characteristic of a structure, unforeseen yet inevitable consequences, one leading to another. These ramifications demonstrate the inescapable power of events to structure thought. The daughter cannot escape the thought of her father killing the neighbour, the father cannot escape the thought of his daughter killing herself, the mother cannot escape the thought of both dying. I, in turn, cannot escape the story as a whole. On reading it I experienced what Heidegger calls a dynamis, a “meaningfulness,” which led to the creation of the artworks detailed below. There is thus a chain which links each event in the story to myself and the artworks that I made in response. This presentation is another link added to this chain.

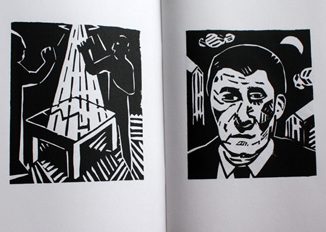

Witness

Along with my experience of the story, there arose a question: how does one make art that represents such violent events and their ramifications? This is the problem that circulates constantly within the project. My immediate response to this question was to adopt a style from art of the past, in this case early twentieth century German Expressionism; many of whose works deal in similar themes of violence and angst; employing a graphic style of representation, and a use of primitive mediums such as woodcut and linocut. Taken together, the style of Expressionism can be understood as a signifier of violence; a style that is also detectable in the original newspaper story, written in the form of demotic reportage. My adoption of the style of Expressionism led to the creation of a series of images, made using the simple medium of linocut printing, each of which depicts a different “act” in the story, and a different actor.

The linocut medium imposes the style of Expressionism onto the images, which in turn allows them to be seen as unified within a simple linear narrative that reflects the sequence of events. In this thinking, the relation between the original report, and its visualisation in the artworks, is essentially one of exchange; in which one form of expression is swapped for another – linocut printing for writing. In this manner the work, in its totality, has the form of a trope, in particular a metonym; the story of violence is the cause of the images, the images become the story. An exchange which is enabled through the Expressionistic style common to both.

A trope places us before a problem, which we are asked to resolve. The problem detected at the outset of the project, understood as a problem of representation, is answered by the adoption of the style of Expressionism as a signifier of the violence inherent to the world of the protagonists. Yet, for Deleuze, imposing a unified style onto a work of art, hides its true structural unity of difference. In Proust and Signs, he says that the role of style is not to impose a unity onto a work of art; but to create viewpoints on the artworks’ difference, without altering its “fragmentation;” the work’s unity is something that comes afterwards.

This is apparent in the next stage of the creation of this first body of work, when these images were collected into a small publication, Witness. Each image is arranged in a portrait/event pair, each portrait imagining what they cannot escape from. The father’s encounter with the neighbour from the viewpoint of the father; the daughter’s death dive from the viewpoint of the mother; the killing of the neighbour from the viewpoint of the daughter. This is the style of the publication, which enables the images to escape the unifying style of Expressionism, opening them up to interpretation, by placing them in pairs and in series. These viewpoints do not give the work its unity, this is derived from what Deleuze calls the “formal structure of the work of art,” which creates a unity as a “final brushstroke.” The publication creates what Deleuze calls a transversal viewpoint, which cuts across the other viewpoints, and connects them, but without unifying them. The transversal is a totalising and unifying point of view, which does not totalise or unify that which it puts into communication. It is a dimension that is added to the work’s other dimensions of style, surface, image etc. It is like the narrator in a novel, who sits above the events they comment on, without affecting them. The communication that the transversal causes, extends beyond the images in their pairs, it travels back to the newspaper story and on to works yet to come. Its view also extends across my essay, “Witness the Gift of Seeing” that accompanied the images in the publication.

This essay, written after the creation of the artworks, draws upon Martin Heidegger’s essays, “The Origin of the Work of Art” and “Time and Being,” and asks, how can, what Heidegger calls the dynamis, and what Deleuze calls the sense of the original written story, be preserved and carried over into the artworks, from where it is in turn transmitted to readers/viewers. My answer to this question follows Heidegger, in that dynamis is understood as something given by the logos, the discursive nature of the newspaper story. This understanding led to the concept of “witness” of the work’s title. I theorised that both the original newspaper story and the artistic images bear witness to the fatal events detailed. Collected into a single work, they call upon viewers and readers to witness and to then bear witness to the events that unfold before them.

This concept of witness appears to replicate Deleuze’s concept of viewpoint, justifying my adoption of the style of Expressionism. Implying that the viewpoint that each work expresses is what its style is a sign of – violence. Yet, this understanding is brought into question by Deleuze’s theory of style. In Proust and Signs he says that the parts, which style maintains, excludes the “logos both as logical unity and as organic unity.” (163) Therefore the question, raised by my encounter with the newspaper story, theorised as a problem of representation, to be answered by the adoption of a style is misleading. Deleuze says that representation is the site of a “transcendental illusion,” DR 265 pdf) which covers over the difference that style aims to maintain. This leads to the question, raised by my encounter with the newspaper story, being theorised as a problem of representation, to be answered by the adoption of the style of Expressionism, which represents the a priori condition of violence. The true problem is the one that representation always fails to answer, the problematic nature of encounter.

The next body of work, The Aviary, again addresses the relationship between thought and practice, not from the perspective of style, but from the perspective of encounter, what Spinoza calls the occursus, the “lived encounter” of bodies, an encounter that forces us to think. Whereas the work of Witness is a publication, the work of The Aviary is an exhibition of paintings. The origin of The Aviary project is an image, taken from Plato’s Theaetetus, which I encountered in Heidegger’s commentary on Plato’s dialogue in The Essence of Truth. This image is the link that connects it to the thinking in the previous project, in that it has the form of a trope, in this case a simile. Heidegger describes a trope as a sinn-bild, a “sensory-image,” (ET 12) which encourages us to think by hinting at a meaning beyond what it shows. A simile, therefore, is a clue to seeing, which places us before an as yet unresolved problem. In this manner it appears to offer the possibility of a resolution to the original problem of representation, given in my encounter with the newspaper story.

Plato’s simile shows an aviary, at first empty, which is filled by its owner releasing birds into it. Once released into the enclosure, the birds act in different ways, some gather in large flocks, some in small groups, while others are more solitary. The owner can, at any time, re-enter the aviary and grasp hold of a bird within. This simile demonstrates that we can know and not know the same thing. The birds are like memories we possess, stored at the back of our mind, and therefore absent from us. We can make these memories present to us in the same way as the aviary owner enters the aviary and takes hold of a bird, that is we revisit our memories, and, by grasping hold of one, bring it to the front of our mind. The significance of the birds in the varieties of ways in which they present themselves, singly and in flocks etc, is that this refers to how a being is experienced as a concrete entity, and as a composite of universals.

The Aviary exhibition replicated this simile. The gallery was understood, as being like an aviary, as a container, which is at first empty, which is then filled by the addition of paintings of birds, based on illustrations, which I found in a book from 1880, Fulton’s Book of Pigeons. My paintings were displayed, singly and in groups, replicating Plato’s description of the birds as solitary or as gathered in flocks. Visitors to the exhibition played the role of the aviary owner. In viewing the exhibition, the spectators put each work into Being in two ways, either as something actual displayed before them, or as something recalled when not standing in front of the work. Therefore, in this thinking, beings, including the incorporeal sense of the work, are objects of recall, which are assembled before us by the natural exercise of our senses and our faculties working together, i.e. common sense.

This implies that sense is something stored along with its bodily cause, both of which can be extracted by an effort of will. Yet, in this model, the dynamis of encounter, which forces us to think, is missing. Objects of encounter work on us, not us on them, they give “rise to a sensibility with regard to a given sense.” (DR 139 pdf) The object is therefore a sign by which the given is given. It is in sensibility’s encounter with being as a sign, that it “finds itself before its own limit;” Deleuze’s “passion of thought.” The various objects of encounter, the newspaper story, lino prints, painted images, are thereby signs experienced as bearers of a problem. The thinking instigated by a trope, appears inadequate to its resolution. Both metonym and simile invite us to think the problem it places before us, and to solve it; whereas the thinking intrinsic to encounter, forces us to think that which can only be thought. It is a thinking that does not solve the problem, but affirms it in its disjunctive character of difference. This is enabled by the transversal, which takes our viewpoint beyond what is before us.

The adoption of a style, as in Witness, as a signifier of extremes of emotion and violence, is, in the end, inadequate to the problem of difference experienced in the presence of the artwork and of the newspaper story. Yet, something new does emerge from The Aviary, which leads to another understanding of the relationship between style and image. In his book on the painter Francis Bacon, Deleuze defines the materiality of painting as a combination of traits and patches. Traits are lines of paint invested with meaning, Deleuze talks about Bacon’s painted lines introducing “traits of animality,” into a painted head. In the case of my work, the lines of paint are first thought as traits of birds, i.e. feathers, which then become traits of the pigeon loft, the grain of the wood from which it is constructed. Finally the lines become traits of a painting itself: the weave of canvas. Therefore the painted lines, superficially a stylistic convention, have a meaning, each small line is a sign, which is open to interpretation. This is also the case for the other aspect of painting that Deleuze identifies, the patch of colour, which, he says, appeals to the “shifting semblance,” the “vague and impalpable essence of things.” (177). My thinking on the patches of colour in my paintings reflects this, here colour is thought as clouds, indeterminate, shape-shifting, like the meaning of the lines of paint, capable of change. Therefore, what was thought as the tropic nature of images, by which they refer to something beyond the image, are now understood as signs, interpreted through the style of the work.

This thinking gives the possibility of experimentation through the material practice of painting. An experiment in thinking that unites thought and practice in the artworks that it creates. This is captured in Landscape Without Birds. In this work, painted on board, the brushstrokes form the woven structure of a canvas painting, under which the cloud of colour, which forms the image, sits. Therefore, in this work the material structure of painting is reversed, canvas does not support the image, the image carries the canvas; the style of this work, therefore, releases a paradox, which informs the following bodies of work in this project.

This stylistic paradox of reversal is the hidden link in the chain of the project as a whole, it is the paradoxical element, which Deleuze, in Difference and Repetition also calls the dark precursor. As the two-sided thing = x and word = x, the aliquid, “something,” the dark precursor circulates invisibly within and between series, bringing them together. The dark precursor also has the capacity to structure psychic experience, therefore its introduction is the key to the project’s drive to communicate the psychic conditions of the protagonists. These understandings are developed in a further three bodies of work, all under the rubric of Father, Mother, Daughter. These works return to the theme of the newspaper story explored in Witness. Because of time constraints I shall discuss each of these bodies of works briefly in terms of structure.

Father, Mother, Daughter I is the main work of this project overall. Made up of three series of three paintings. Each series depicts one of the protagonists, each in a different mis en scene, drawing upon the meaningful stylisms of a painting from The Aviary project: Landscape Without Birds (above). The first of these stylisms is the use of bands of colour to structure each painting, a hidden aspect of Landscape Without Birds. A further stylism is that the works place each figure in either cloud-like patches of paint, or under the open weave of fabric, or both.

The display of the works, in part, continues the objective thinking of The Aviary exhibition, but now, instead of starting from objects of recall, it begins from paintings theorised as objects of encounter, experienced in repetition. We experience each object, each painting and each series of paintings as successive, we see one after the other, in this way the first resembles the second and the second resembles the third.

In this encounter we also experience a resonance between the series, explicated by the style of the works, and made present in what Deleuze calls our “intersubjective unconscious.” The viewing subject is split up and distributed between conditions past, and conditions present; the unconscious operates in the gap between, putting the figures in the present and their actions in the past into communication by the operation of symbolic figures within the work. These are the clenched hand, the ghostly face, the angular building, the towering bridge etc. These symbolic figures signify the past in the present, as such they form the delay, in which the before and after coexist, as the resonance of something past that has a presence. Therefore, these works are unified by the stylistic dark precursor, something hidden that puts them in communication.

The focus of Father, Mother, Daughter II is again on the individual protagonists seen in series, but now these works emphasise the style of the paintings, the images are inside, emerge out of and appear through the painting’s surface. As with Landscape Without Birds, the Father paintings exist under but also on the canvas structure formed by the painting’s brushstrokes. The Mother paintings replicate the precursor’s hidden banded structure, lines of paint communicate through the form of the figures, while over each is a touch of reality, a twisted piece of paper, a scrap of fabric with images drawn on it, a child’s toy. The Daughter images put us in touch with the previous body of work, i.e. Father, Mother, Daughter I, when they merge with the symbolic images of wardrobe (closet) door and heart-shaped pendant, which dominates in the final image. In all these works, their images exist (or should I say subsist) as incorporeal events at the surface. They have neither the substance and accidents of subterranean bodies, nor the universal and particular of the elevated. They bring together the painting as a literal and figural denotation, i.e. a state of affairs, and the sense it expresses at the surface.

Father, Mother, Daughter III, the project’s concluding experiment, returns to the simplicities of printmaking, in this case woodblock prints. These works, like all of Father, Mother, Daughter, are, in the end, expressions of sense, the surface connection of material and thought, practices of thinking and practices of making. The images form a structure: heterogeneous series of symbolic objects, portrait heads, which are put into communication by the paradoxical element, the knife-in-hand image in repetition. The images create singularities, derived from their method of construction – an initial ink drawing onto absorbent paper, which fixes the flow of the ink at its edge. The resultant image places “internal and external spaces into contact, without regard to distance.” (LS 106) This means that their distances, both internally and externally, are topological. This drawing forms a template for the cutting of the woodblock. In this manner the images are affirmed in their external and internal difference, some printed onto paper, some printed directly onto a wall. The terms of each series come together in a synthetic disjunction; on one side of which is neutrality and on the other a “fruitful” production, together they form a conjunction of casualities. This is the realm of impersonal and pre-individual singularities, i.e. prior to the formation of the consciousness of the I and the self. This is art as a “sense-producing machine, in which nonsense and sense are…co-present to one another within a new discourse.” (LS 109)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the five bodies of work exist as part of a structural whole put into communication by the element of style, underpinned by the order of the symbolic enabled by the works’ transversality. This means, from the many works made during the course of this project, many configurations in many future exhibitions, and many new works are possible.

Derek Hampson